Wherein we have the appearance of the All-Time Team’s Mystery Man

This installment of the Brewers All-Time Team will look at third base! Reminders:

- We’re looking for the best individual season at each position, not the best career

- Players can only be used once

- A player must have played more games at the given position in the given season than any other position

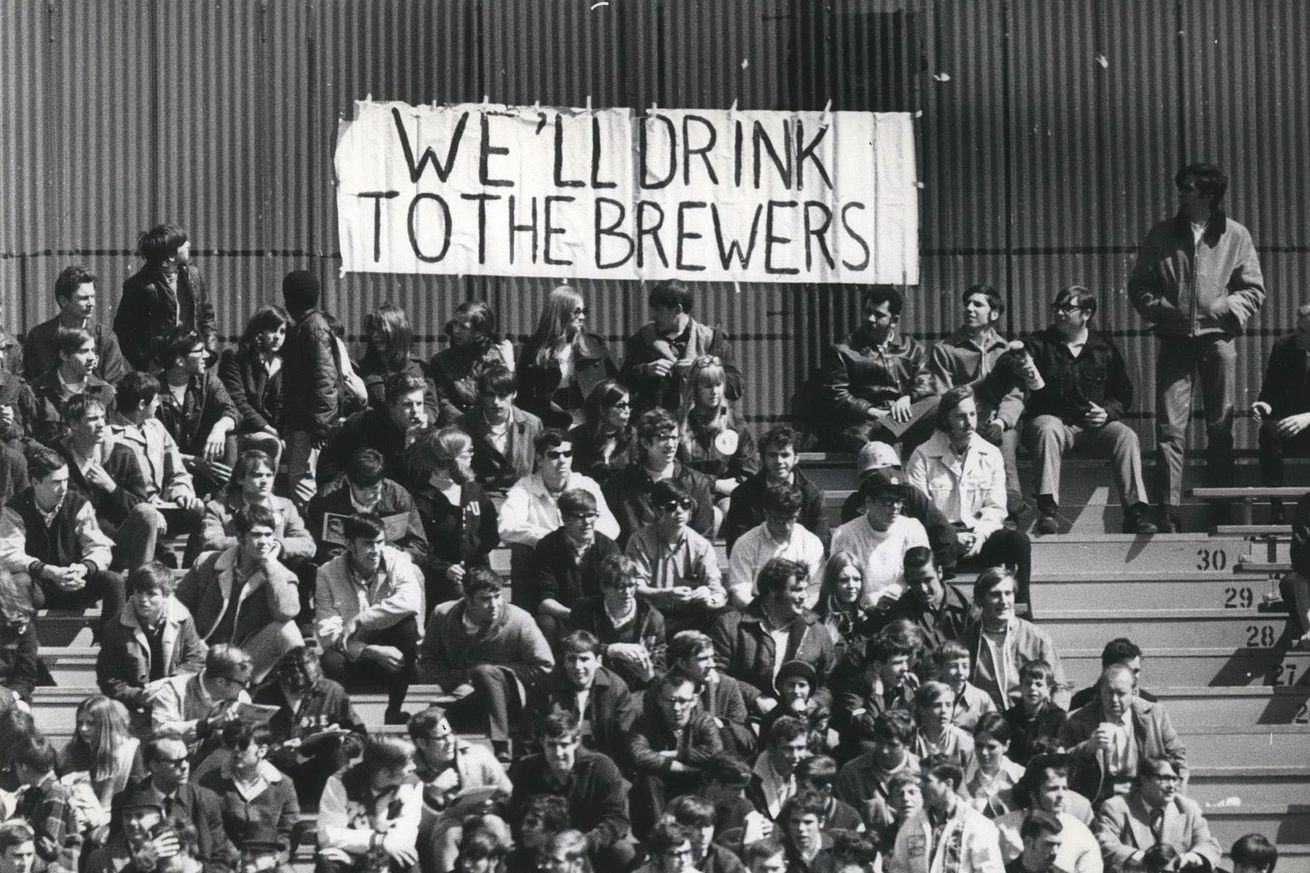

So far, we have covered catcher, first base, and second base. This week continues with one of the lesser-known team members as we look at the hot corner. (Lesser-known enough that the USA Today database contains no images of him on the Brewers! So instead, enjoy this photo from the Brewers’ first-ever game in Milwaukee.)

Third Base: Tommy Harper, 1970

154g, .296/.377/.522, 146 OPS+, 35 2B, 31 HR, 82 RBI, 38 SB, 77 BB, 7.4 bWAR, 6.8 fWAR

To find the best season in Milwaukee Brewers history at third base, you must return to the very beginning, where you will find an incredible outlier season put together by a nearly forgotten figure in franchise history.

Tommy Harper was the third pick in the American League portion of the October 1968 expansion draft, making him the second official Seattle Pilot after first-round pick Don Mincher. A few months later, Harper led off on April 8, 1969, in Anaheim for the first official at-bat in franchise history (in which he doubled and scored, giving him more franchise firsts).

By the time he got to the Pilots, Harper was only 28 but had seven seasons under his belt already, having come up with Cincinnati at the tender age of 21. Harper’s Reds tenure was statistically volatile; he showed promise (such as his 1965 season when he led baseball in runs scored while hitting 18 homers and stealing 35 bases at a good clip) but lacked consistency. Cincinnati traded him across Ohio to Cleveland before the 1968 season, and he spent one disappointing season there before Seattle took him in the expansion draft.

Harper’s 1969 season was historic in its own right. He did not hit (.235 with a .311 slugging percentage), but he did walk 95 times and he stole an eye-popping 73 bases to lead the majors. Obviously, that was a franchise record… but it still stands, the only record of any note in franchise history that is held by a Pilot.

When the Pilots moved to Milwaukee after just one season in Seattle and became the Brewers, Harper went with them (and led off again 364 days after his first Seattle appearance, giving him the first at-bat in Brewers history) and had a season that is difficult to explain. In 1970, at age 29, Harper played 154 games and put up the following numbers: .296/.377/.522 (a 146 OPS+), 35 doubles, 31 home runs, 82 RBI, 38 stolen bases, 77 walks, and 104 runs scored. In his entire career, in no other season did Harper ever hit more than 18 homers or 29 doubles. He never hit above .281 and his .522 slugging percentage was the best of his career by 100 points. He also played what was, by our best modern guesses, decent defense at third base, especially surprising given that Harper spent most of his career as a mediocre-to-bad corner outfielder.

That 1970 season was worth 7.4 WAR according to Baseball Reference. Harper had a 4.8 WAR season in 1973 and 3.7 in 1965, but never had more than 2.2 in any other of his 15 seasons. He made his only All-Star team and finished sixth in MVP voting. It didn’t really help the Brewers, as they were in just their second season and finished at 65-97-1; Harper had more than 5 WAR more than any other position player on the team (though closer Ken Sanders did have a monster season out of the bullpen).

I’m sort of fascinated by outlier seasons, and please excuse my (not-all-that) brief aside. It’s one thing for players who flash some talent to have a couple of good months, but for something to come together for a whole season, that’s a different story. It happens in a variety of ways: you might get a Jurickson Profar 2024 season when a former top prospect makes good way after everyone gave up on him. Or you might get a season like Rico Petrocelli in 1969 when an otherwise solid player suddenly and inexplicably hits 40 homers and has an OPS+ that’s 45 points higher than any other season in his career. Or maybe you look at Brady Anderson’s 50-homer 1996 (which falls into a separate category of, er, suspicious seasons—though it should be said that there is no evidence that Anderson ever used PEDs). A few more of my favorite outlier seasons:

- Our own Bill Schroeder in 1982 hit .332 in a career-high number of plate appearances; he never hit above .257 in any other season.

- Norm Cash in 1961 led the American League in OPS, and I’d like to remind you that this was the year that Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris were chasing Babe Ruth’s home run record. Cash hit .361/.487/.662 with 41 homers, a league-leading 193 hits, and 9.2 WAR; it’s one of the best seasons ever by a first baseman. He had a solid career but never had more than 5.4 WAR in any other season.

- Lonnie Smith in 1989 led the NL in OBP and hit more than twice as many homers as in any other season, giving him 8.8 WAR.

- At 22 in 1941, Pete Reiser led the NL in WAR, runs scored, doubles, triples, and two of the three slash-line triple crown categories. He wasn’t as good in 1942, then missed three years for the war, and was not the same player when he returned even though he was only 27. (There is a whole category of guys who have a big early impact and then disappear—like Pat Listach—but this one is especially extreme.)

- Outlier seasons are more common among pitchers, but a good one that occurred in Milwaukee was when Mike Caldwell was the American League’s second-best pitcher in 1978 (behind only a historically great year from Ron Guidry). Caldwell was 22-9 with a 160 ERA+ that year but had only three seasons with an ERA+ over 100 in his 14-year career. Almost 45% of his career bWAR came in ‘78.

- Another pitching example is when Esteban Loaiza led the AL in strikeouts with 207 in 2003 after having never had more than 137 in a season. He had 7.2 WAR that year and never had more than 3.8 in any of his 13 other seasons.

Back to our guy! Harper played one more season with the Brewers before being included in a gigantic trade that had all sorts of big names but one that mattered more than the rest: it was the trade that brought George Scott to Milwaukee, where he became the franchise’s first major star. Harper had one more good season with the Red Sox in 1973 and bounced around the league through 1976 before retiring at age 35 when he finished his career with over 1,600 hits, 250 doubles, 400 stolen bases, and 25 WAR.

The one other name that needs to be mentioned at third base is, of course, Paul Molitor. If you read the explanation of our All-Time Team’s second baseman, you’ll see that Molitor’s 1979 season was the choice there, and there’s a deeper explanation of why in that essay. Long story short: using Molitor at second base and Harper at third gives us the best across-the-board value, and in the only seasons in which Molitor was obviously better than he was in 1979, he was a DH more than any other position. It also should be said that while Molitor had one or two better offensive seasons as a Brewer than Harper did in 1970, he never had a season that approached Harper’s in terms of total value (as measured by WAR).

Beyond Harper and Molitor, the Brewers have had several very solid third basemen in their history (you could argue that the Brewers have had more “good” third basemen than any other non-pitching position, even if they don’t all bring top-tier star power) but none who approached the heights of that magical 1970 season.

Also considered: Molitor in 1982 and 1988; Jeff Cirillo’s 1997 and 1998, in which he played Gold Glove-caliber defense and hit .288 with 46 doubles (1997) and .321 with 194 hits (1998); Sal Bando’s 1978, when he turned back the clock and had a classic prime-Bando-in-Oakland season; Aramis Ramirez’s 2012, when he hit .300 with 50 doubles, 27 homers, and 105 RBI; and Don Money’s 1974, his first All-Star season, in which he was solid in all facets of the game.