Our series continues with the team’s weakest position

Our All-Time Brewers Team continues today at second base! Reminders:

- We’re looking for the best individual season at each position, not the best career

- Players can only be used once

- A player must have played more games at the given position in the given season than any other position

We’ve already done catcher and first base. Time to look at second base, where we made some compromises.

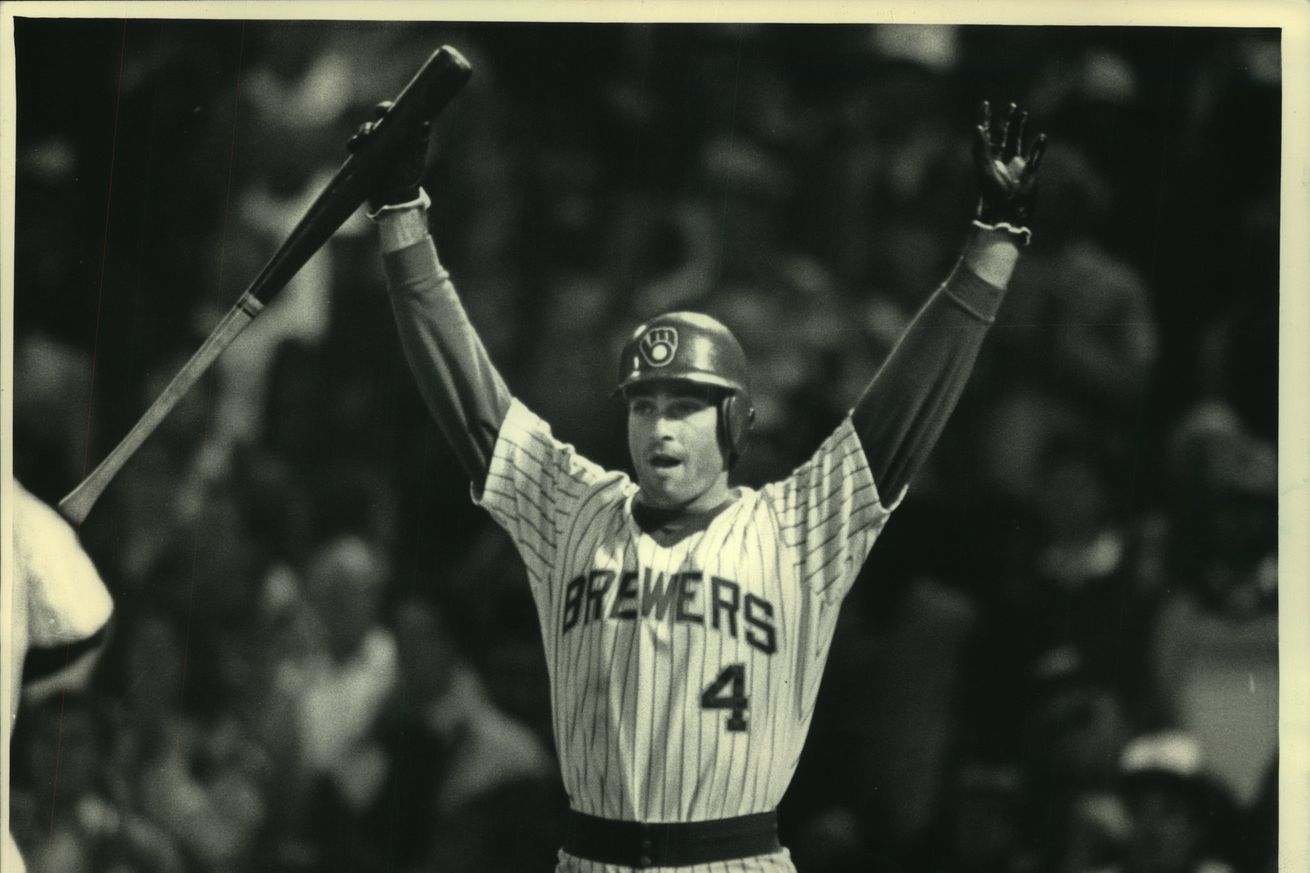

Second Base: Paul Molitor, 1979

140g, .322/.372/.469, 126 OPS+, 27 2B, 16 3B, 9 HR, 62 RBI, 33 SB, 5.6 WAR

There’s a funny thing about the history of Brewers’ second basemen: the two best seasons ever at the position are from guys who were not really second basemen. What became clear when doing this project was that the position definitely lacks compared to the others—it is, without a doubt, the weakest in club history. So, those two seasons that ended up at the top came from guys who you would call major stars of the franchise, but both spent far more time at the hot corner.

The one chosen here is Paul Molitor’s second season in 1979, and it will require a bit of explanation, so bear with me. You likely do not think of Molitor as a second baseman, but we’ll get into that a bit later. The second-best season by a second baseman in club history belongs to Don Money, who—like Molitor—played way more third base than anything else for the Brewers…except in 1977 when he had one of his best years while playing second.

But you are a wise, historically aware Brewers fan, and you might be saying to yourself “there’s no way that 1979 was Molitor’s best season as a Brewer.” Well, you would be right, but here is where my arbitrary rules come into play. Molitor’s best season in Milwaukee was 1987… but he played more DH than anywhere else that year. He did also have excellent offensive seasons late in his Milwaukee career (he was better offensively in 1989, 1991, and 1992 than he was in any of his pre-1987 seasons) but in ‘89 he was playing third base and in ‘91 and ‘92 he was mostly at DH again.

The next question here is “why don’t you just put him at DH?” That’s valid for you to ask, but here’s where I ultimately ended up: Molitor’s 1979 is the best season ever by a Brewer second baseman, so putting him at DH and using a lesser season at second base hurts the team. Further, I decided just not to use a designated hitter in this All-Time Team, for two reasons: number one, the Brewers only had a DH for about 60% of their history (1973-98, 2020, and 2022-present); and number two, the pickings after Molitor are extremely slim (you’re very likely looking at Dave Parker’s 1990 season when the 39-year-old Cobra hit .289 with 21 homers but, because of low walk totals and his status as a full-time DH, had only 1.1 WAR).

Molitor also certainly had a couple of years worthy of consideration at third base, but I decided to go with his 1979 season at second in order to create the best team possible. Molitor’s 1979 season is better than Money’s 1977 season, and there were far more strong seasons in the team’s history at third base, so with no DH spot, the team that maximized value was the one with Molitor at second, which is, I will reiterate, the best season ever by a Brewers second baseman, even though it isn’t Molitor’s best. I hope that makes sense.

Anyway, back to that 1979 season. Molitor was only 22 and hadn’t yet been a professional baseball player for two years. He’d been picked by the Cardinals out of high school late in the 1974 draft, but he chose to go to the University of Minnesota instead and became one of the top prospects in the country. Milwaukee took him third overall in the June 1977 draft and sent him to Single-A Burlington for the rest of the season, where he promptly hit .347/.457/.504 in 64 games. He broke camp with the Brewers in 1978 and, having never played above A-ball, hit .273 with 26 doubles and 30 stolen bases in 125 games. He got three first-place votes for Rookie of the Year, finishing second to Detroit’s Lou Whitaker.

Molitor was a positional nomad who played shortstop in college (he has the rare distinction of being on the only Topps rookie card with more than one Hall of Famer: the 1978 “Rookie Shortstops” card, which features Molitor, U.L. Washington, Mickey Klutts, and Alan Trammell), but he was blocked there with Robin Yount in the fold. So he instead played second, where he appeared regularly for his first three seasons. Bizarrely, Molitor spent his (injury-abbreviated) 1981 season in the outfield, but in 1982 he landed at third, which would be his home for most of the 1980s. Though he finished his career with more appearances as a designated hitter than at any other position, a lot of that can be attributed to the fact that Molitor was a great old player; he didn’t really start playing DH full-time until 1991 when he was 34. It’s just that he kept playing for another seven years after that.

This leads to a quick myth that needs busting, the myth being that Molitor was a bad defensive player. This is wrong. He wasn’t Frank White out there or anything, but the best modern estimates of defensive value we have show Molitor as a solid defensive infielder up through the 1990 season when he switched to DH. Eight years spent as a more-or-less full-time DH sent his career defensive value into the tank, but for more than half his career, Molitor was perfectly fine as a defensive infielder.

So, in 1979, Molitor was at second base, and the Brewers had a young team rich in talent coming off a 93-win season (the first winning season in team history) and ready to contend. Cecil Cooper was approaching his prime at first base. Yount was beginning to hit his stride. Money was still around playing a utility role, as was the young Jim Gantner. The veteran Sal Bando was at third, coming off an excellent 1978 season. Ben Oglivie, Gorman Thomas, and Sixto Lezcano all played well in the outfield, giving the Brewers one of the most potent trios in the league.

Molitor was in the middle of it all. At just 22, he gave the 1979 Brewers what was arguably their best all-around season. He hit .322 and was second in the American League with 16 triples. Though he was still finding his way as a base stealer, his speed was obvious, and he stole 33 bases. He was pretty good in the field. The Brewers set a franchise record with 95 wins, a total they would not surpass until 2011.

New numbers tell us that Molitor had 5.6 WAR in 1979, which is tied with Lezcano (who had a monster year in which he hit .321/.414/.573 with 28 homers in 138 games) for the team lead. It was a harbinger of future success for Molitor, who just continued to improve. Aside from injury-shortened seasons in 1981 and 1984, he was an above-average hitter every year from 1979 until his retirement after the 1998 season.

I mentioned this earlier, but Molitor’s 1979 season wasn’t his best. By OPS+, his best season came in 1987; he played only 118 games that year but hit .353/.438/.566 and led the league in runs scored and doubles despite missing over a quarter of the schedule. By WAR, Molitor’s best year was 1982, a season in which he led the majors in runs scored and successfully stole 41 bases in 50 attempts while playing adequate defense at third base.

But his most consistent run of success came late in his career: from 1991-94, Molitor had an OPS+ of at least 141 each season, a run that included a World Series MVP in 1993. Of course, that wasn’t with the Brewers; Bando, now the Brewers’ general manager, let Molitor walk after the team’s surprisingly successful 1992 season. Bando cited Molitor’s age—he turned 35 during the ’92 season—but didn’t bring up the fact that he’d hit .325 (and led the league in hits and triples) in 1991 and .320 (with 31 stolen bases) in 1992. Molitor said he wanted to stay in Milwaukee, but Bando didn’t make much of an effort, Molitor left, and the team went into a tailspin that lasted years. Many fans—my friend Vince’s dad chief among them—have never forgiven Bando.

Given the historical depth the Brewers have at third base and the lack of a DH for this project (in a vacuum, Molitor’s 1987 season is definitely his best as a Brewer), it made the most sense to use him as the squad’s second baseman. As you’ll see below, there’s not a whole lot of great other options, and putting Molitor there makes the best overall team, as you’ll see later.

Also considered: Money’s 1977, in which he hit .279 with 25 home runs and played good defense; Brice Turang’s 2024, when he combined Platinum-Glove-winning defense and elite baserunning with sporadically competent hitting; Willie Randolph’s 1991, when the former Yankee star inexplicably had arguably his best offensive season as a 36-year-old on his fourth team in four years; Jim Gantner’s 1983, when he combined his best offensive season with typically good defense; and because he’s maybe my favorite Brewer ever, Rickie Weeks’ 2010, when he really found his way as a potent offensive force and was healthy for the whole season. Also a shoutout to my first favorite Brewer, Fernando Viña, who in 1998 had a 114 OPS+ and made the All-Star team.